Contents

Introduction:

Today, April 4, 2024, marks a special day – it’s the Qingming Festival in China, a national public holiday. This festival is often translated into English as Chinese Tomb Sweeping Day, The Pure Brightness Day of China, or Chinese All Souls’ Day. However, I believe the transliterated Qingming Day captures its most significant symbolic essence. It brings to mind the poem “Qingming” by the Tang Dynasty poet Du Mu:

清明时节雨纷纷,路上行人欲断魂。

借问酒家何处有,牧童遥指杏花村。

Recited in Chinese, it sounds exceptionally beautiful and melancholic. Essentially, the poem depicts a rainy Qingming day that leaves travelers heartbroken and despondent. I’m disheartened and yearn for a drink alone. Seeking a tavern to shelter from the rain, I ask a shepherd boy, who points to the distant Apricot Blossom Village. Ah, so it’s “there.” Of course, this interpretation doesn’t appear in the original poem, but anyone who hears it understands, as “Apricot Blossom Village” represents a figment of human imagination.

This is why Qingming Festival, alongside Dragon Boat Festival, Spring Festival, and Mid-Autumn Festival, is considered one of China’s four major traditional festivals. Now, let me tell you what is the Qingming Festival in China.

Part One: Why is it called the “Qingming Festival”?

The traditional Qingming Festival in China dates back to the Zhou Dynasty, boasting over two and a half thousand years of history. Initially, Qingming was an important solar term signaling rising temperatures and the perfect time for spring plowing and sowing. Later, as Qingming’s date approached the Cold Food Festival – a day for ancestral tomb sweeping and a fire ban in folk traditions – the two gradually merged. The Cold Food Festival thus became an alternative name for Qingming and a custom of the season, where no fires were lit and only cold food was eaten.

By the Guangxu period of the Qing Dynasty, the old saying in “A Hundred Questions for the Seasons” went: “At this time of all things growing, all are clean and pure, hence the name Qingming.” Indeed, this sentence captures the essence of what all Chinese wish to express in their hearts.

Today, “Shangsi and Han Shi” – two festivals close to the Qingming period – have merged. With widespread customs of tomb-sweeping, ancestral worship, and outings near the Qingming Festival across China, it has gradually evolved into a traditional Chinese festival for commemorating ancestors with tomb-sweeping and offerings.

Part Two: What are the Cold Food Festival and Qingming Festival in China?

The Cold Food Festival and Qingming Festival are two closely linked yet distinct festivals in history. Initially, the Cold Food Festival was established to commemorate the loyal courtier Jie Zitui, with its main custom being the ban on fire and consumption of cold food. On this day, people would not cook with fire but eat cold food instead. The Qingming Festival, on the other hand, primarily involved ancestral worship and tomb-sweeping, along with outings. Over time, as the dates of these two festivals drew near each other, their customs and activities began to merge.

The Story of the Cold Food Festival

Legend has it that during the Spring and Autumn period, there was a loyal courtier named Jie Zitui in the state of Jin. After helping Duke Wen of Jin regain his throne, Jie was granted fertile land. Later, Duke Wen forgot Jie’s contributions, and Jie chose to live in seclusion in the mountains, refusing to serve in court again. Regretful, Duke Wen wanted to find Jie and sent men to set fire to the mountains, hoping to force him out. To demonstrate his resolve to die rather than surrender, Jie Zitui embraced his mother and perished in the flames. Grieved, Duke Wen ordered a three-day fire ban throughout the nation to commemorate Jie’s loyalty. Since then, people have eaten cold food and refrained from lighting fires on this day each year in memory of Jie Zitui, marking the origin of the Cold Food Festival.

From the Cold Food Festival to the Qingming Festival

By the late Eastern Han Dynasty, the custom of a fire ban on the Cold Food Festival had become widespread among the people, who would not only refrain from cooking but also engage in tomb-sweeping and ancestor worship on this day. By the Tang and Song dynasties, the Cold Food Festival had become a fixed festival, with its customs and significance further enriched to include commemorating loyalty, filial piety, and activities like spring outings and kite flying.

In the Tang Dynasty, the Qingming Festival had been established as an important spring festival, with people engaging in tomb-sweeping and ancestor worship on this day. As the Cold Food Festival and Qingming Festival were close in date, people often conducted commemorative activities on both days, gradually merging the customs of the Cold Food Festival into the Qingming Festival, combining the activities of the two festivals.

In the Song Dynasty, the Cold Food Festival and Qingming Festival had essentially merged into one, with Qingming Festival becoming the primary festival name. The Cold Food Festival’s customs, such as the fire ban and consumption of cold food, were integrated into the Qingming Festival’s celebratory activities. Thus, in many regions, the Qingming Festival also inherited the traditions of the Cold Food Festival, becoming a comprehensive festival that not only commemorates ancestors and conducts tomb-sweeping but also includes activities like spring outings and kite flying to celebrate the arrival of spring.

Therefore, although the Cold Food Festival was once an independent festival in history, its customs and activities were eventually integrated into the Qingming Festival, merging the two into one.

Part Three: Popular Activities during Qingming

Qingming is a time when Chinese people show reverence for nature and ancestors. This tradition dates back to ancient times and remains highly significant today. Tomb-sweeping and ancestor worship are two major activities for commemorating deceased loved ones. People remove weeds around the graves and add fresh soil to show care for the departed. Of course, for many Chinese families, tomb-sweeping is essential.

Activities during China’s Qingming Festival:

*Offer sacrifices to ancestors 祭祖/上供

*Burn joss paper 烧纸钱

*Tomb-sweeping 扫墓

*Kite flying 放风筝

*Spring outing 踏青

Part Four: The Custom of Burning Joss Paper

During China’s Qingming Festival, the belief and custom of burning joss paper have a long history and continue to influence the present. Burning joss paper, from the perspective of the living, carries significant symbolism: while people rely on money for goods exchange and securing life and survival in the world, the deceased, in another world, also need to live and survive, making various items like joss paper, gold and silver paper, and differently valued hell bank notes a means of goods exchange in the underworld.

The activity of burning joss paper must be carried out from start to finish; one must wait until the paper is completely burned before leaving, showing respect for the ancestors while preventing fire hazards or the wind scattering the paper, which could sadden the deceased ancestors if snatched by wandering ghosts.

In modern times, it is best to burn joss paper at the cemetery for deceased loved ones, ensuring it is received even in large cities. If worshipping distant relatives, burning joss paper at crossroads or quiet, open spaces can reduce urban disturbances.

Part Five: “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” and China’s Ancient Qingming Festival

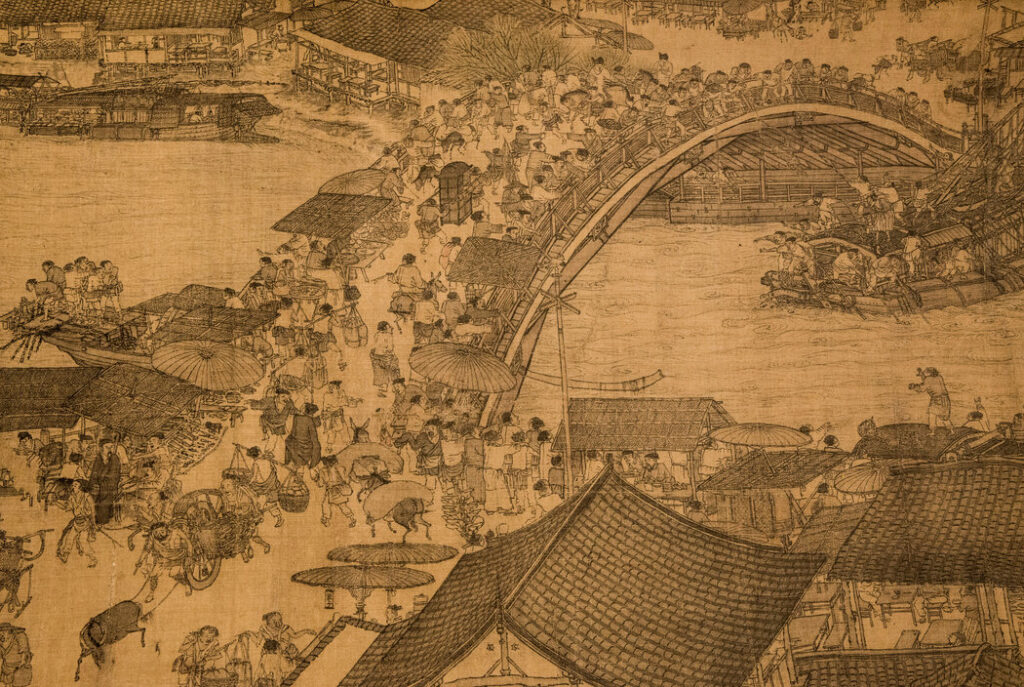

“Along the River During the Qingming Festival” is a long scroll painted by Zhang Zeduan of the Northern Song Dynasty, a masterpiece in ancient Chinese painting known for its intricate details, bustling cityscapes, and lively depictions of human activities. The painting showcases the prosperity of Bianliang, the Northern Song capital (present-day Kaifeng, Henan), during the Qingming Festival, conveying the festive atmosphere of celebration and prosperity through scenes of busy streets, lively bridges, and diverse city life.

By illustrating the lifestyle, busy markets, and festive activities of Kaifeng’s residents, the painting vividly reflects that the Qingming Festival is not only a time for commemorating ancestors and sweeping tombs but also a festival filled with vitality, joy, and social interaction. However, as history evolved and time passed, the whereabouts of the original version became unknown. Today, what people can see are mostly later copies and reproductions of “Along the River During the Qingming Festival.”

Conclusion:

As time flows ever onward, the Qingming Festival is not just a cultural tradition, it’s a bridge spanning past to future’s wide expanse of imagination. Whether in distant lands afar or on familiar soil we reside, each of us in our own ways remember those who’ve left our side, celebrating too spring’s arrival and nature’s rejuvenating stride. Just like the words “Qing” and “Ming” imply: As the rain softly falls, Tomorrow lies clear in sight!

Published by: Mr. Mao Rida. You are welcome to share this article, but please credit the author and include the website link when doing so. Thank you for your support and understanding.